Thailand’s love for urban gardening

The quiet systems that keep Bangkok and Thai cities unexpectedly green

Walk down nearly any street in Bangkok, and you’ll notice something that doesn’t quite match the usual portrait of a Southeast Asian megacity. Between the concrete shophouses and glass towers, beneath the elevated train tracks and along the motorcycle-clogged pavements, plants are everywhere.

Not manicured landscaping or municipal flower beds, but an unruly profusion of potted trees, herbs in plastic buckets, flowering shrubs squeezed into the margins between buildings and roads. On balconies five storeys up, tomatoes ripen in old paint tins. At ground level, chilli plants guard doorways, their bright red fruits catching the afternoon light.

This greenery doesn’t announce itself. It simply exists, woven so thoroughly into the urban fabric that locals barely register it. But to an outsider’s eye, the density is startling. Thailand’s approach to urban gardening grows plants the way other places accumulate road signs or noise constantly, almost unconsciously, as if vegetation were a natural byproduct of human settlement rather than its opposite.

The question is why. What makes Thailand different? The answer isn’t simple. It’s not just climate, though that helps. It’s not solely culture, though belief plays a part. Instead, it’s the convergence of several forces, environmental, practical, spiritual, and historical, that have turned plant keeping from a hobby into something closer to a civic habit.

Understanding why Thailand is so green requires looking at how these systems work together, reinforcing one another until growing things becomes less a choice than a condition of daily life.

On this page

| Section (Click to jump) | Short summary |

|---|---|

| The climate advantage | Thailand’s tropical conditions remove most barriers to plant growth, making cultivation low-effort and nearly automatic in urban life. |

| Gardens as infrastructure | Home gardens function as practical systems for food, shade, medicine, and resilience rather than decorative landscaping. |

| The kitchen pharmacy | Culinary herbs double as everyday medicine, blurring the line between cooking, healthcare, and household self-sufficiency. |

| Plants for luck | Auspicious plants add a symbolic layer to urban greenery, reinforcing planting as protection, aspiration, and cultural alignment. |

| The discipline of the Shrine | Spirit houses anchor daily routines of care, embedding plant maintenance into household rhythm rather than conscious effort. |

| Sacred trees | Religious practices such as tree ordination extend moral protection to vegetation, shaping long-term conservation through belief. |

| Policy and the public realm | Urban greening policies reinforce household practices, normalising vegetation as part of streets, infrastructure, and shared space. |

| When systems stack | Climate, utility, belief, and policy reinforce one another, creating a city where plants appear everywhere without deliberate planning. |

| A quiet continuity | Thailand’s urban greenery persists not as a trend, but as an unbroken extension of long-standing domestic and cultural systems. |

The climate advantage

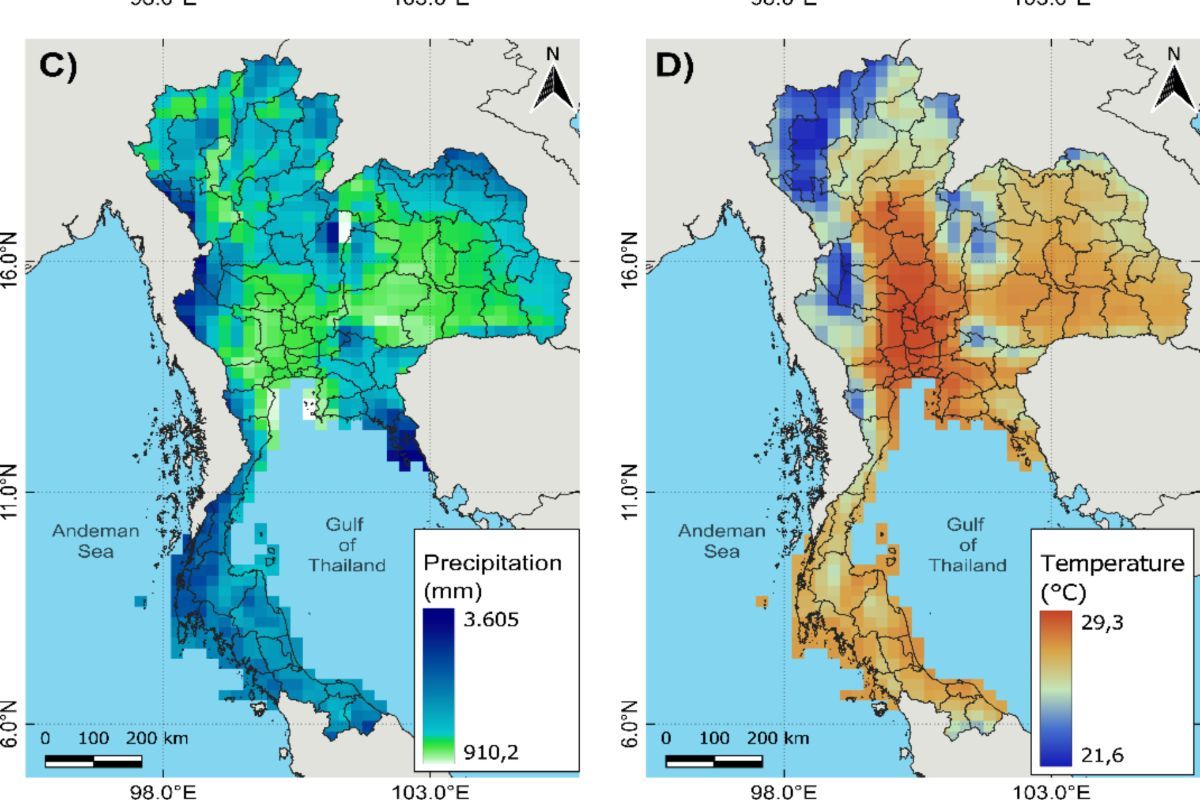

Start with the obvious advantage: Thailand sits in the tropics. High temperatures and intense sunlight mean that plants grow fast and die slowly. The rainy season delivers enough water that irrigation, whilst helpful, isn’t strictly necessary for survival. Soil doesn’t freeze.

Growing seasons don’t stop. A cutting stuck in damp earth will root within days. A seed dropped in a crack in the pavement may sprout before the week is out.

For anyone who has tried to keep houseplants alive through a northern winter, this climate is a revelation. In temperate cities, plant care demands attention to fertiliser schedules, grow lights, winter storage, and careful monitoring of soil moisture.

In Thailand, the environment absorbs much of that labour. Plants survive despite neglect, not because of meticulous care. This changes behaviour in ways that make urban gardening throughout Thailand nearly effortless. The cost, in both time and money, drops low enough that plant ownership becomes nearly frictionless.

University agriculture departments in Thailand have long treated urban gardening and home planting not as a lifestyle trend but as a practical response to available resources. Extension offices distribute guides on backyard cultivation.

The assumption is that households will grow things because they can, not because they’ve decided to take up gardening as a hobby. The baseline expectation is growth.

Gardens as infrastructure

But ease alone doesn’t explain the particular character of Thai greenery. Plenty of tropical places don’t have plants clustered around every doorway.

What sets Thailand apart is how households use these plants. Thai home gardens studied extensively by ethnobotanists and agronomists over the past few decades aren’t ornamental.

They’re working systems. A single small plot might contain fruit trees for shade and snacks, herbs for cooking, medicinal plants for home remedies, and flowering species reserved for religious offerings. These aren’t separate categories. They overlap, often in the same pot.

This functional density has deep roots. In rural Thailand, the home garden has long been a form of household infrastructure, providing food security, income supplements, and traditional medicines. As urbanisation accelerated through the late twentieth century, the practice didn’t disappear. It adapted.

The ground shrank, but the logic remained. Urban gardening in Thailand moved plants into containers, onto rooftops, into schoolyards and narrow alleyways. What had been a rural strategy became an urban one, compressed but not abandoned.

Researchers who study urban agriculture in Thailand tend to describe these spaces not as nostalgia for village life but as extensions of household resilience. The plants aren’t decorative. They’re useful. This distinction matters. When plants serve a purpose beyond aesthetics, their presence doesn’t need justification. They’re kept because they work.

The kitchen pharmacy

Consider the herbs. In Thai cooking, fresh ingredients aren’t a luxury; they’re standard. Basil, lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime, pandan, chilli. These aren’t garnishes, but they’re the foundation of flavour. And many of them double as medicine.

Lemongrass for fever, basil for digestion, and pandan for calming. The boundary between food and pharmacy is thin, sometimes nonexistent.

Because of this overlap, plants cluster near kitchens. Keeping them close reduces effort. A cook can reach out and pluck a few leaves without interrupting the rhythm of meal preparation. A stem can be snapped off and crushed for a home remedy. The plant doesn’t need a label. Its function is understood.

This creates a kind of casual abundance. One pot may hold several uses. Several pots exist because each solves a small, recurring need. Over time, the collection grows not through deliberate planning but through accumulation. Someone brings home a cutting. A neighbour offers seeds. A market vendor includes a free seedling with a purchase. Each addition is minor, but the cumulative effect is a household surrounded by greenery.

Plants for luck

Then there’s meaning. Thai households don’t just grow plants for utility. They grow them for luck. Known as our auspicious plants, certain species are believed to bring prosperity, protection, or harmony. Some are associated with career success. Others with family stability or health. The logic isn’t always transparent to outsiders, but the practice is widespread.

Thai-language guides on auspicious planting circulate widely, especially around housewarmings, business openings, and religious holidays. These aren’t fringe publications.

They’re mainstream, sold in bookshops and shared on social media. The plants themselves aren’t exotic. They’re common species money trees, lucky bamboo, certain palms chosen for their names or symbolic associations rather than their rarity.

This layer of belief justifies adding plants even when the functional need is already met. A household may have herbs for cooking and shade trees for cooling, but auspicious plants occupy a different category.

They’re not redundant. They’re insurance, or aspiration, or both. The motivation isn’t aesthetic excess. It’s symbolic alignment. And once that logic is accepted, there’s always room for one more pot.

The discipline of the Shrine

The spirit house adds another mechanism entirely. These small shrines, found outside homes, businesses, and public buildings across Thailand, serve as residences for protective spirits. They require regular maintenance. Fresh flowers, leaves, and garlands. These offerings must be replaced, often daily. The surrounding area must be kept tidy. Watering becomes habitual.

Even households that approach these practices casually find themselves locked into a rhythm. The physical presence of the shrine anchors a routine. Plants near these spaces are rarely neglected for long, because neglect would signal disrespect.

Care becomes part of the household order rather than conscious gardening. And once that rhythm is established, adding another pot doesn’t significantly increase effort. The habit is already there.

Sacred trees

In public space, religion shapes vegetation in a different way. Thailand has a documented tradition of tree ordination, in which Buddhist monks wrap trees in saffron cloth to designate them as morally protected beings. The act is symbolic, not legal, but it works.

Cutting an ordained tree becomes socially unacceptable, even taboo. Communities enforce this through shame rather than law, but the effect is real, and the trees remain.

Academic studies of environmental conservation in Thailand often cite tree ordination as an example of how religious symbolism can support ecological restraint. The practice originated in rural areas, where it protected forests from logging.

But the underlying logic that trees deserve moral consideration has seeped into urban culture as well. It influences how trees in villages, temples, and city streets are treated. Once a tree is seen as worthy of protection, it tends to stay.

Policy and the public realm

Not all greenery is informal. Bangkok and other Thai cities run explicit greening programmes. The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration has, in recent years, promoted tree planting for shade, heat reduction, and air quality.

Community gardens, school gardens, and roadside plantings appear in district-level plans. One prominent initiative, commonly called the Million Tree Planting Project, set a target of planting one million trees by 2025. The programme focuses on streets, canals, public land, and partnerships with private property owners.

Maintenance contracts explain why plants beneath elevated rail lines and along major roads appear consistently watered and trimmed. This isn’t accidental greenery. It’s policy, executed at scale. But these programmes don’t replace household planting, they amplify it.

Public greenery reinforces the sense that plants belong everywhere, not only in designated parks. The visual message is clear: this is a city where vegetation is normal.

When systems stack

What strikes visitors isn’t any single factor but their accumulation. Climate lowers the cost of growing. Household systems normalise plant keeping. Food and medicine make plants useful. Belief makes them meaningful. Policy makes them visible in shared space.

In places where only one or two of these elements exist, plant density remains limited. In Thailand, urban gardening practices stack, and the result is a landscape where greenery appears both intentional and incidental, purposeful and casual, planned and accidental, all at once.

A pot placed beside a doorway may be there for shade, for luck, for cooking, or simply because the plant thrives in that spot. Often, it serves all four purposes simultaneously. The categories aren’t exclusive. They reinforce one another. A useful plant can also be auspicious. An auspicious plant can also provide food. The overlap doesn’t create confusion. It creates abundance.

A quiet continuity

None of this is new. Studies of Thai households from the twentieth century describe similar patterns, though in different forms. What has changed is scale. Urban growth compressed space, but it didn’t erase habits. Plants adapted to containers.

Traditions adapted to balconies. The logic of the home garden, mixed use, functional density, and symbolic selection survived the transition from village to city. It didn’t survive intact, but it survived.

The persistence of greenery in Thailand is therefore not a reaction to modern environmental anxiety. It’s not a recent trend or a response to climate awareness campaigns. It’s the continuation of a system that never fully separated nature from domestic life.

Plants weren’t banished to parks or restricted to weekends, but they remained part of everyday, integrated into routines that predate air conditioning and high-rises.

This helps explain why the greenery feels different from what you see in other cities. In many places, urban nature is contained in parks, gardens, and designated green spaces. It exists in opposition to the built environment, carved out and defended.

In Thailand, the relationship between urban spaces and gardening is more porous, and Plants occupy the gaps. They fill awkward corners, cling to walls, perch on windowsills. They don’t wait for permission. They simply grow, and people let them.

What looks excessive from the outside is, within the country, ordinary. A Bangkok apartment balcony crowded with pots isn’t a statement. It’s normal. A shophouse front lined with herbs and flowering shrubs isn’t a conscious design choice. It’s what shophouses look like.

The greenery isn’t remarkable until you step back and realise how rare this is elsewhere, how few cities maintain this density of informal, household-scale vegetation alongside their infrastructure.

The lesson, if there is one, isn’t that other places should copy Thailand. Climate alone makes that impossible. But Thailand demonstrates what happens when urban gardening becomes embedded in multiple systems that align to support plant keeping: when the environment makes it easy, when households find it useful, when culture makes it meaningful, and when policy makes it visible.

The result isn’t a garden city in the conventional sense. It’s something stranger and more resilient, a city where plants have never stopped being part of the furniture, where greenery persists not despite urbanisation but alongside it, adapted and ongoing.

Late afternoon in Bangkok. The heat is beginning to ease. A woman waters the pots outside her shophouse: basil, lemongrass, and a small lime tree.

A few doors down, someone hangs a fresh garland on a spirit house. Further along, beneath the train tracks, municipal workers tend the roadside plantings.

The plants themselves are unremarkable. What’s remarkable is that they’re there at all, thriving in the margins, sustained by habits so ordinary they barely register as choices. The city grows. The plants grow with it. That’s just how it works.

Related articles:

• Spirit houses in Thai culture

• See flowers blooming every December at Suan Luang Rama IX Flower Festival

• The best national parks near Bangkok

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: