Inside Bangkok’s gun trade at Wang Burapha, Thailand’s firearms district

A look at civilian ownership, regulation gaps, and why reform remains elusive

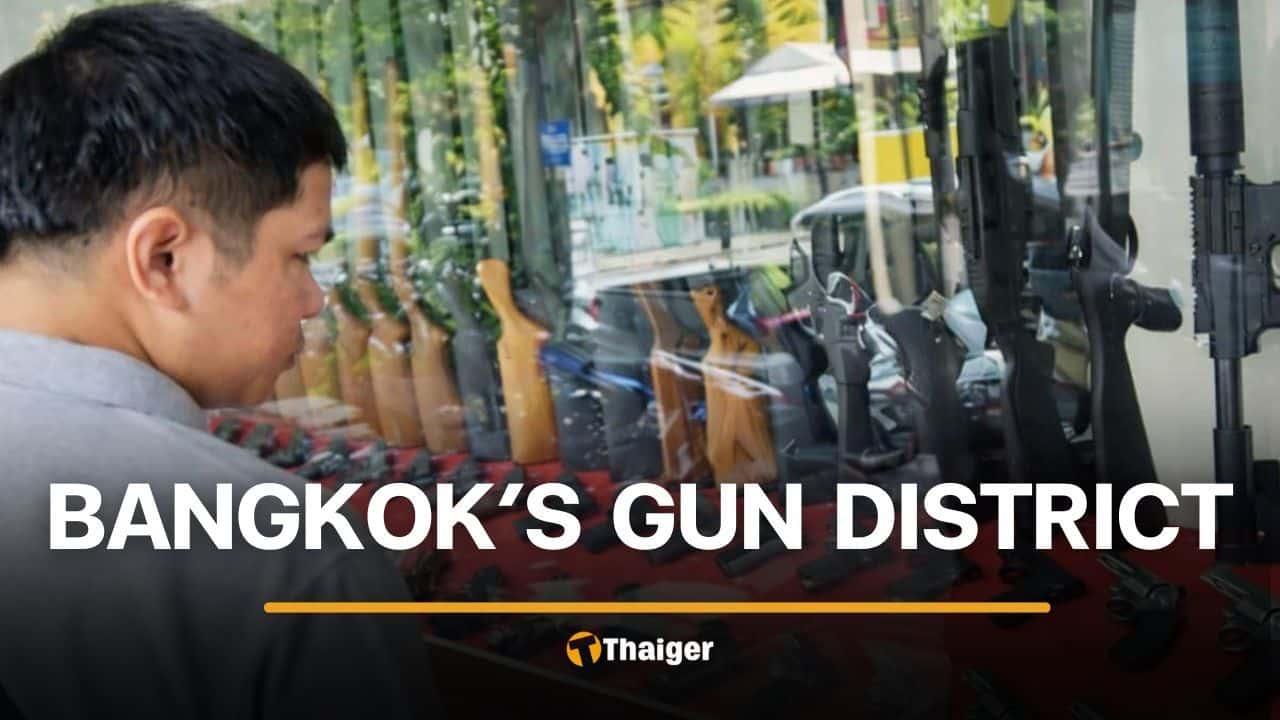

In central Bangkok, a few blocks from the gilded spires of the Grand Palace, shop windows display an unexpected inventory that few visitors expect to see. Where tourists anticipate silk scarves or smartphone cases, they’re filled with Glocks, CZs, SIGs, Kimbers, Colts and Berettas arranged in neat rows, hunting rifles propped against the glass, boxes of ammunition stacked like tea tins.

This is Wang Burapha, known simply as Bangkok’s gun district, where firearms have been sold openly for more than seventy years.

Nearly eighty licensed gun shops line these timeworn streets. Behind glass counters, revolvers rest on velvet, shotguns hang from pegboards, and clerks discuss calibres and permits with casual expertise.

The neighbourhood is both ordinary and exceptional: a place where the commerce of weapons proceeds as matter-of-factly as the commerce of anything else.

On this page

| Section (Click to jump) | Short summary |

|---|---|

| A permissive system | Explores how Thailand’s firearms laws operate in practice, allowing widespread civilian ownership through licensing and parallel markets. |

| A culture of self-reliance | Examines social attitudes toward firearms, particularly the belief that personal protection is an individual responsibility. |

| When the shootings came home | Details how high-profile mass shootings shifted public perception and forced national attention onto gun access. |

| The paradox endures | Reflects on how legal gun commerce continues alongside rising violence, highlighting unresolved tensions in Thai society. |

A permissive system

Wang Burapha’s gun shops began appearing in the late nineteen-forties, shortly after Thailand passed its first comprehensive firearms law in 1947. The legislation established a framework for civilian gun ownership, permits were required, but attainable.

Many of these businesses are still family-run, passed down through generations and the shops never left, even as the surrounding entertainment district faded.

On paper, Thailand’s gun laws are restrictive. The 1947 Firearms Act limits ownership to those over twenty years old, requires permits for each weapon, and allows guns only for self-defence, sport shooting, hunting, or property protection. Penalties for unlicensed possession can reach ten years in prison.

In practice, the system has proven remarkably permissive. The Interior Ministry processes applications through more than nine hundred district offices nationwide. Applicants need proof of employment, income, a clean record, and a fixed address. “The rules are strict,” said Police Major Chavanut Janekarn, a criminologist.

But if you have a proper job, no criminal record and enough money, it is relatively easy to get approved for a licence. Applications often clear in two to three months. The licensing fee is five baht or twenty cents.

Roughly one hundred thousand new guns are registered each year. As of 2021, the official count stood at about six million privately owned firearms, one for every ten people. But estimates of unregistered guns range from four million to well over ten million. The actual number circulating in the country likely exceeds official records by a wide margin.

What sustains this parallel market is partly cost. A new Glock 9mm that retails for four hundred dollars in the United States can cost more than three thousand dollars in Thailand, inflated by import taxes and dealer markups.

However, the black market offers an alternative.

In October 2023, a fourteen-year-old obtained a blank gun online, modified it to fire live ammunition, and used it in a shooting at Siam Paragon mall. Two people were killed that day.

The state itself contributes to the arsenal. In 2009, the government launched a; welfare gun; program, allowing civil servants and officials to purchase firearms at a thirty-to-forty-per-cent discount. Hundreds of thousands of weapons have been distributed this way.

Critics note that some recipients resell their discounted guns for profit. After a national outcry in 2022, police proposed freezing the program. As of 2023, the proposal had not been acted upon.

A culture of self-reliance

Thailand is often called the Land of Smiles, but beneath the surface, courtesy runs a pragmatic scepticism about public safety. Surveys consistently rank Thailand near the bottom in Southeast Asia for trust in law enforcement. This sense of insecurity appears to fuel gun ownership.

Anchistha Suriyavorapunt, a criminology researcher at Mahidol University, notes that many Thais, particularly in rural areas, view firearms as a practical necessity for protecting property, deterring intruders, and responding when help may not arrive in time.

In provincial towns, it is unremarkable for a household to keep a rifle or shotgun. Village headmen have long been among the first to receive gun permits, a visible marker of authority.

Phairoj Kullavanijaya, a sixty-eight-year-old retired civil servant, keeps a 9mm pistol on his belt while tending to his fruit farm. “I’ve always been interested in guns,” he said. Naturally, a man would want to own a gun for protection. He bought his through the welfare gun programme and has never fired it outside a shooting range. Still, he wears it.

This comfort with firearms exists alongside brutal statistics. In 2016, more than three thousand people were killed by guns in Thailand, a rate nearly eight times higher than in neighbouring Malaysia. Gun violence is often attributed to gang feuds, the drug trade, and business disputes.

These explanations tend to frame shootings as isolated incidents rather than symptoms of a broader issue. For a long time, that framing allowed a certain complacency. Gun deaths happened elsewhere in distant provinces, in the criminal underworlds, not in the ordinary rhythms of middle-class life.

When the shootings came home

On February 8, 2020, a Thai army sergeant walked into a shopping mall in Nakhon Ratchasima carrying an assault rifle. By the time security forces killed him, twenty-nine people were dead.

It was Thailand’s deadliest mass shooting by a lone gunman. The government promised reforms. Security at military arsenals was tightened. Beyond that, little changed.

Two and a half years later, on October 6, 2022, a former police officer entered a childcare centre in Nong Bua Lamphu and killed thirty-six people, including twenty-four children. Most were preschoolers, killed during nap time. The country grieved. Calls for stricter gun laws intensified.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha ordered a crackdown on illegal weapons. His cabinet floated proposals: psychological evaluations for gun applicants, tighter background checks. A year later, none had been enacted. The rules are the same because the rules never changed, one gun dealer in Wang Burapha remarked.

Why the inertia? Police Major Chavanut Janekarn offered one answer: The gun business sector is very large in Thailand, and there are lots of gun dealers that have close connections to the government… to the police and to the military.

Then came Siam Paragon, a gleaming mall in the heart of Bangkok, frequented by tourists and the Thai elite. The fourteen-year-old shooter made the attack impossible to dismiss as a provincial anomaly. This time, the government acted more decisively.

Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin announced an indefinite suspension of new gun licenses and a plan to reclassify blank guns as firearms. By early 2024, the Interior Ministry had halted new carry permits. Whether these measures will hold remains unclear.

Meanwhile, reported firearms offences surged from around twenty-four thousand cases in 2018 to more than eighty-seven thousand in 2022. Many incidents do not make headlines: bar fights that turn lethal, feuds between students settled with pistols, business disputes that end in shootings. Gun violence in Thailand is both spectacular and mundane.

The paradox endures

Back in Wang Burapha, the shops continue as they have for decades. Under fluorescent lights, customers handle revolvers, test the weight of a Beretta, and negotiate prices. The clerks are professional and knowledgeable. They see themselves as legitimate businessmen serving a legal market. And they are.

Yet the district embodies a paradox. It represents a regulated, transparent system where civilians can legally purchase firearms. But its very existence reflects a society that has normalised deadly weapons to an unusual degree. Thailand has the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in Southeast Asia. By some estimates, one in four Thais may have access to a firearm.

This is a country that has never been colonised, never experienced modern warfare on its soil, yet has more gun deaths per capita than some conflict zones. Public attitudes may be shifting. After each tragedy, there have been louder calls for reform, particularly from younger, urban Thais.

Yet the conversation remains measured, focused on better regulation, stricter background checks, and mental-health screenings rather than on bans.

This reflects a distinctly Thai approach: a preference for incremental adjustment over confrontation, for consensus over conflict. It also reflects a recognition that guns are deeply woven into the social fabric.

For now, Wang Burapha endures. A customer slides his palm across the walnut grip of a revolver, and the shopkeeper explains the permit process and the price. Outside, a monk in saffron robes pads by. In the distance comes the crack of gunfire from a shooting range.

It is an ordinary afternoon in Bangkok’s gun district, a place in Thailand where the machinery of violence operates in plain sight, part of the city’s fabric, neither hidden nor entirely acknowledged.

Note: Foreigners are prohibited from entering these firearm shops.

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: