Phuket Books: The all-American horror tale of a tough childhood

PHUKET: In 1989, Tobias Wolfe published his block-breaking memoir This Boy’s Life, later made into a movie with Robert DeNiro and Leonardo DiCaprio. Tobias Wolfe was the mentor of Mary Karr who published her own masterpiece memoir in 1995: The Liar’s Club.

These two books about hard-scrabble childhoods marked the emergence of a new literary era and unleashed a floodgate of memoirs, but few have reached the standards that Wolfe and Karr set.

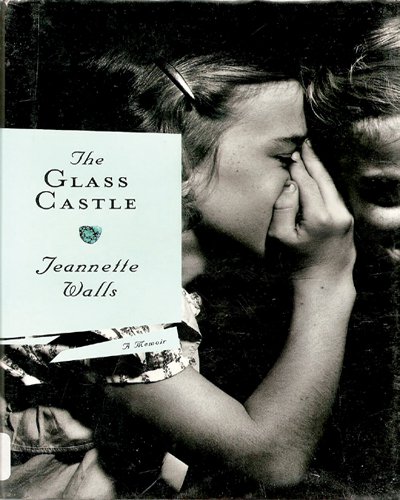

You might think Karr had a tough life growing up in the oil refinery town of Port Arthur, Texas, the daughter of an alcoholic father devoted to bars and pool halls, and an equally alcoholic mother devoted to poetry and painting. But along comes Walls with her memoir of a much worse life, The Glass Castle (Scribner, New York, 2005, 288pp).

Karr’s father was an oil worker who kept a roof over her family’s head and food on the table. Walls’s father was an electrician who was constantly fired, drank up what money there was and left his four children hungry. Her mother was a poet and painter and equally indifferent to her children.

They bounced around little desert towns in the American West before settling in Welch, her father’s home town in the mountains of West Virginia’s coal country. He becomes the town drunk as the children sink deeper into hunger, cold and raw poverty, and the mother remains dreamily above it all.

“We fought a lot in Welch,” the author writes. “Not just to fend off our enemies, but to fit in. Maybe it was because there was so little to do in Welch; maybe it was because of all the bloody battles over unionizing the mines; maybe it was because mining was dangerous and cramped and dirty work, and it put all the miners in bad moods and they came home and took it out on their wives, who took it out on their kids, who took it out on other kids. Whatever the reason, it seemed that just about everyone in Welch – men, women, boys, girls – liked to fight.”

There are innumerable scenes of melodrama, like the Christmas when the drunken father stood up in church and cursed out the priest and then went home and set the Christmas tree on fire along with all the presents. The mother put up with the father because she is Catholic and refuses to go on welfare because it will be bad for her children’s character.

“Mom could be wise as a philosopher, but her moods were getting on my nerves,” Walls writes. “At times she’d be happy for days on end, announcing that she had decided to think only positive thoughts . . . But the positive thoughts would give way to negative thoughts, and the negative thoughts seemed to swoop into her mind the way a big flock of black crows takes over the landscape, sitting thick in the trees and on the fence rails and lawns, staring at you in ominous silence. When that happened, Mom would refuse to get out of bed.”

Lori, the eldest, vows to escape to New York City after high school graduation. She and her siblings save up money in a piggy bank which the father breaks, of course, and spends on drink. But Lori does escape, along with Jeanette, and then Daniel and Maureen. Later, their parents follow them to New York and become homeless people.

Much of this tale is simply unbelievable. But even if true, the characters remain puppet figures. The parents show none of the nuance, color, humor and contradictory shades of Karr’s parents. And the writing is vastly inferior. You can have a tougher life than Karr did, but this does not make for a better memoir.

Predictably enough, The Glass Castle went on to be a big best seller, with glowing reviews in women’s magazines like Vogue and Glamour. The minutiae of poverty is well described: the ramshackle rooms, the improvised furnishing, the threadbare clothes and the constant scavenging for food, but the heart isn’t moved as in the memoirs of Karr and Wolfe. This is a memoir by the numbers.

The book is available online or by ordering through all good bookshops in Phuket.

— James Eckardt

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: