Light shined on blackouts – Phuket Diving

PHUKET: The death of PADI professional and freediving enthusiast Denis Lipatov last month brought into sharp focus the specter that continues to haunt the sport of freediving – shallow water blackouts (click here for article).

Even the term “shallow water blackout” is rife with confusion within the freediving community, and even more so within the scuba diving community and general public, according to Richard Wonka, Southeast Asia representative of the International Association for the Development of Freediving (AIDA).

The term, often used to describe a variety of freediving accidents, has for many become a catch-all that fails to adequately describe the circumstances leading to an unconscious freediver. Rarely do freediving accidents lead to fatalities. In fact, taking the safety precautions that are taught in any freediving course make a staggering difference.

In an attempt to clarify and demystify shallow water blackouts, Divers Alert Network (DAN) recently developed a new terminology for blackout accidents. Most fall into three categories: duration induced blackout, ascent induced blackout and hyperventilation induced blackout.

Asking why we black out leads to an even more basic question… why do we have the urge to breathe? Most of us, professional scuba divers included, keep it simple: because we need oxygen – and for anyone but elite freedivers, that is simply wrong.

Without extensive training, we are not even aware of our oxygen levels, but we quickly register changes in our carbon-dioxide levels. The urge to breathe is actually the desire to exhale, rather than to breath in.

Normally, as we exhale we are breathing out vast amount of usable oxygen. However, that unmonitored supply of oxygen is exactly what keeps us conscious above and below the water’s surface.

Our carbon-dioxide level can give us clues to determine our oxygen supply, but reading these clues requires specialized training.

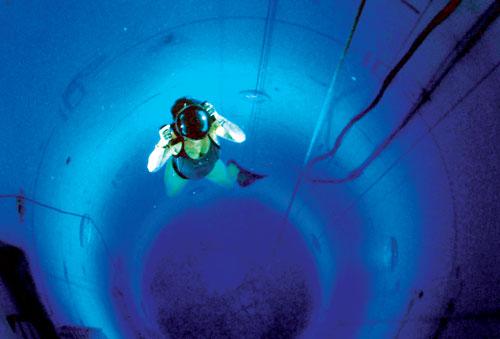

As we descend below the water’s surface the pressure of the water above us increases the partial pressure for oxygen, despite the actual amount of oxygen within our system remaining the same. So, effectively we can function on less oxygen than we could at the surface.

As we ascend, that partial pressure decreases, and though it was sufficient for maintaining consciousness at 20 meters, it is very possible to have used enough oxygen that the partial pressure will drop below the level needed to remain conscious at five meters, leading to a blackout.

Very simply, a person blacks out because the partial pressure of oxygen drops below a certain level.

This is what is described by the term ascent induced blackout. A blackout can also be caused by freedivers pushing beyond their duration limits and unsafely ignoring their body’s carbon-dioxide levels – duration induced blackout. Hyperventilation, which was once taught as a standard practice for increasing freediving times, is another major factor that can lead to a blackout – hyperventilation induced blackout.

Less than ten years ago, scuba diving agencies and their scuba diving instructors, taught hyperventilation as a method for freediving. I too was taught that rapid exhalation allowed me to increase the amount of oxygen I was able to fill my lungs with on my final breath.

This, like many other preconceived notions about freediving, is completely wrong. Hyperventilation simply down regulates the carbon-dioxide levels, which allows you to dive with lower levels of oxygen before your body’s alarm system starts to warn you of worrisome levels of carbon-dioxide.

“They [freedivers after hyperventilating] feel nothing, they feel no warning signs, they feel comfortable because they can not feel the carbon-dioxide increasing and they run out of oxygen without any warning signs,” Richard explains.

There is really only one thing that prevents a freediver from becoming a corpse – a trained buddy on the surface.

“I’ve had to pull a diver out of the water once when there was no sign of distress, no visible sign of anything and then suddenly he was out. I just saw him stop moving and sink to the bottom,” Richard says. It was later confirmed that he had used hyperventilation in an attempt to extend his bottom time.

Many of those who have died freediving alone (none have died during competitions) were not professionally trained, or vowed that “they know the risks, that’s why they are extra careful”.

“That is what every single freediver who has ever died performing the sport says,” Richard says.

“Denis had told me that on several occasions,” Richard said. Divers who utter the phrase are breaking the most basic freediving rule – never freedive alone.

As an untrained freediving enthusiast it is frightening to discover that I fall into this category. With no one wanting to go freediving, I have found peace in gliding above the corals at Ao San on a single breath. Aware of the risk and playing it safe by never going “too” deep or staying down for “too” long, it’s now clear that I simply had no idea what I was talking about.

“It is the most common rationalization of a very real risk, and it’s what everyone who has gone freediving alone and never came back thought. I’d wager very few people went out saying ‘I will go freediving without a buddy because I want to kill myself. Everybody thought they were staying safe, but they didn’t come back,” Richard warns.

— Isaac Stone Simonelli

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: