The fascinating and very odd murals at Wat Borom Niwat

Guest post by Keith Fitzgerald

For years, before I bought a used copy of Kenneth Barrett’s 2013 book, 22 Walks in Bangkok, I believed and often boldly claimed that this capital city has no architecture or art to recommend itself. Yet such ignorance and arrogance were easily overcome. It took just one good book and a willingness to get out and explore the city.

In 2018, I began to discover Bangkok’s history by focusing on Thai and Western architecture – temples, churches, former palaces, government buildings, a prison, forts, and cemeteries.

One afternoon, I was riding in a water taxi on the Phadung Krung Kasem canal, heading from the stop near the Ratchathewi BTS station, and going in the direction of The Crying Bridge, built in 1910 when King Rama V died, which features sculptures of weeping adults and children – and Wat Saket, the Golden Mount temple on a man-made hill in an area that was once used as a cremation site.

In 1851, when he became king, Mongkut ordered the digging of this waterway; its name translates as “the canal upholding the city’s happiness.”

As the long, slim, creaky old water taxi zoomed toward the gleaming golden chedi on the hill, I saw to my left a small temple which struck me as an ideal sanctuary, though I’m not religious at all.

It seemed remote, inaccessible. I’m terrible with maps, don’t speak Thai, and had never been in the area. But I’m determined, and I was eventually able to find out how to get there. It’s a short walk from Bobae Market, and it’s called Wat Borom Niwat.

Built in 1834 on the order of then-prince Mongkut, who served as a monk for 27 years before becoming the monarch, it was then, and remains, relatively secluded. When it was created on Rattanakosin Island almost 200 years ago, it was known as a “dwelling in the forest.”

I have visited there several times and never seen another visitor, and, though I tried to see the inside of the main hall five or six times, it was always closed. I thought that, since no visitors go there, maybe it’s only open when the monks do their daily communal prayers and sutra-chanting.

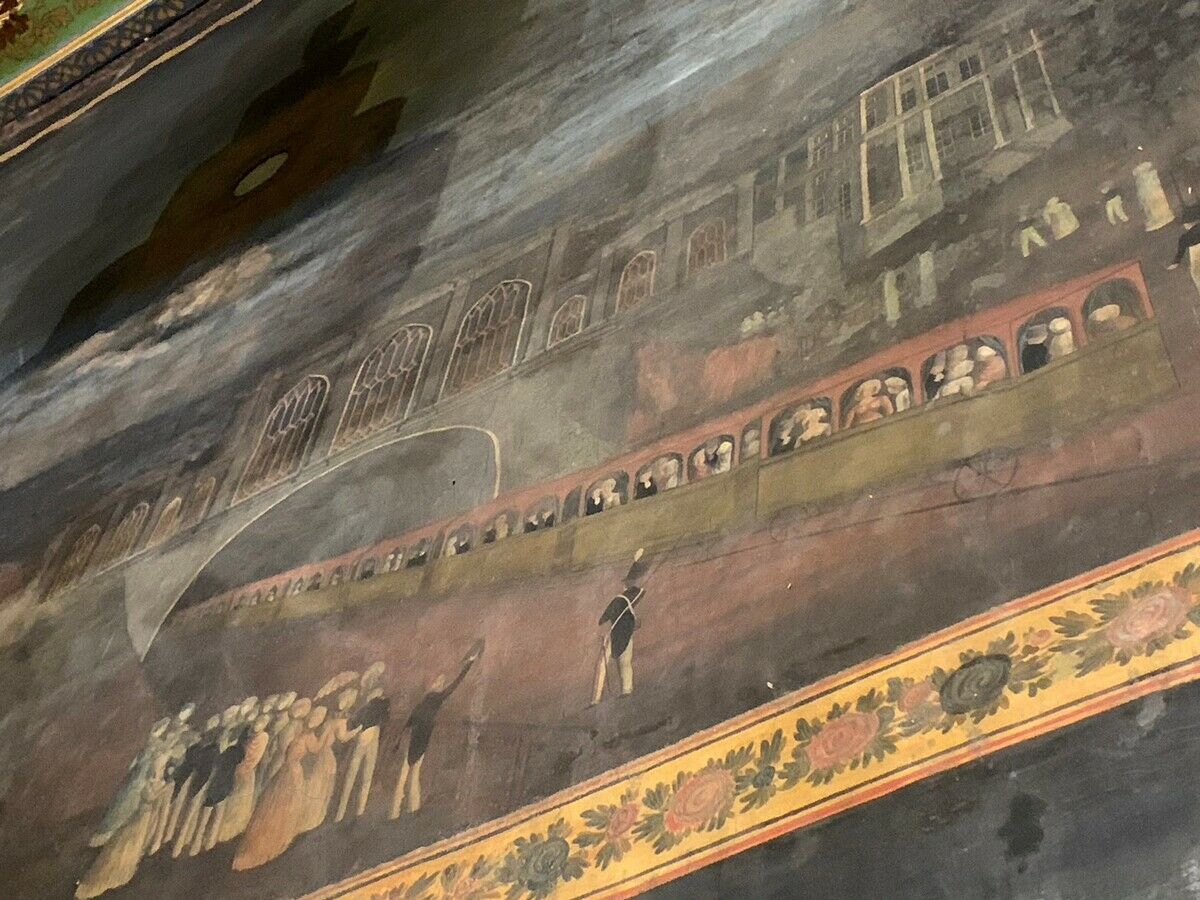

On my sixth visit, I got lucky. The door was slightly ajar, so I walked in and saw a young monk relaxing and using his phone. He welcomed me and invited me to check out the murals, though he was ready to close the building, as it was getting near dusk. The paintings were like nothing I’d ever seen inside a temple, and it turns out that they’re some of the strangest, most innovative works inside any temple in Thailand.

Sometime around 1840, Prince Mongkut commissioned a fellow monk he was friends with, named Khrua In Thong, to paint various scenes inside temples. This was during the reign of Rama III, King Nangklao. Typically, such murals depict the last ten of 547 jataka tales about the previous lives of Buddha before he became Buddha.

We see floating Bodhisattvas, topless nymphs who sometimes fondle each other, battles, nobles or military officers riding elephants, ordinary work and temple life, ascetics, Naga serpents, sick and dying and dead people, and, at Bangkok’s oldest temple, Wat Chong Nonsi, two people having sex in a small enclosure, while, in the centre foreground, the wise man Vidhura-Pandita says goodbye to his various wives and kids before he’s taken away to be killed by the demon Punnaka, who rides a magical horse.

And then there are the creations of Khrua In Thong, especially at this canal-side temple, which were essentially scripted by the future king who Yul Brynner would depict on Broadway and in the classic 1956 film, The King and I.

Mongkut, in addition to founding the Dhammayut sect of Theravada Buddhism, was an intellectual who was fascinated with Western science, culture, religion, and languages. He wanted his artist-monk friend to paint scenes in which Western buildings, technology, and activities would serve as allegorical enactments of key Buddhist themes.

Mongkut spoke English fluently and, during a time when European, British, and American powers were expanding widely in Asia, he sought to learn everything he could about the West, to bring some of its greatest advances to Siam, and to prevent his country from becoming a colony of anyone.

He also made sure that his sons, the princes, got a good Western education, and this is depicted, with emphasis on the future king, Chulalongkorn, in The King and I and in the 1999 movie, Anna and the King.

Mongkut, like the son who would become Rama V, was a great reformer, taking steps to improve the lot of women, and to introduce Western medicine, astronomy, geography, printing, architecture, technology, and dress to the Kingdom of Siam.

The most dramatic artistic expression of this, aside from the many beautiful late-19th and early 20th-century Western buildings throughout the capital, is on the interior walls of Wat Borom Niwat. They are so strange and so modern – from the perspective of Siam in the mid-1800s – as to be nearly freakish.

That first day that I was able to finally get inside the main hall, I had a low-budget Canon camera, and the lighting inside the viharn was low. Also, some of the murals are faded and chipping away. A major restoration by the federal Fine Arts Department is needed. My photos were not good; I asked the monk if I could get his LINE ID so I could come back another time with a better camera, and the interior was fully illuminated. He smiled and said, “Sure!”

A few weeks later, when I was ready, I sent him a message on Line, asking when he’d be free to let me see the murals again. He told me that he was then at a temple in Surin, but planned to return to Bangkok that evening or the next day. He said he’d be happy to let me see Khrua In Thong’s fabulous creations again.

But there was a hitch: He insisted that he had no money to return to Bangkok, and pleaded with me to send him 3000 baht, which he’d repay me when we met. I couldn’t for the life of me understand why he needed that much. A bus to Bangkok is around 400 baht; a train is half that, or less.

Having been scammed many times before in Thailand, I should have just given him an excuse, such as that I was out of work, had no medical insurance, and puny savings. But I was desperate to see and photograph those murals again, and I felt indebted to him for making this dream of mine come true. So, I caved and sent the three grand to him. He said he’d pay me as soon as we met at the temple the next afternoon.

We set a time to meet at Wat Borom. I took the BTS from Punnawithi to Ratchathewi, the canal taxi to the Bobae Market stop, and then walked across the forlorn train tracks to the temple.

When I got there, he was nowhere to be found and would not answer his phone. I panicked, assuming I’d once again been scammed. I searched everywhere for him, going to the main office and calling out to him. The place was deserted. After almost an hour of searching, he finally emerged with a rather devious, detached smile.

No apology. No explanation. He seemed to consider our scheduled meeting and my 3000-baht loan to be of no consequence. It may have been the detachment from money and things which Buddha preached. Or something quite sinister.

He eventually told me that regulations regarding monks prohibit any direct handing of money from a layperson to a man in an orange robe or vice versa, so we had to wait for a seeming security guard to come and handle the return of my 3000 baht.

The monk’s sublime indifference disturbed me. I was sure that, had I not been hellbent on locating him and getting my money back, he would have stayed in hiding, kept my cash, and never let me inside the viharn again.

But, as things turned out, I got my money back, and then he escorted me inside the main hall so I could experience those futuristic murals again.

And here, in good light and with a better camera, is what I saw:

Khrua In Thong was the first Thai artist to employ the 3D linear perspective in painting. His murals are more realistic than what was common before. Though he’d never been to a Western country, these murals are full of European and American buildings, technology, and people.

One shows a train heading underground, though Siam didn’t open its first train line until 50 years later. Most likely, Queen Victoria’s 1856 gift of a model train to King Mongkut inspired this painting.

In another, we see Westerners racing horses. It has been said that this is an allegory of Buddha, the rider in the lead (though it’s actually a white man), who inspires his followers to pursue enlightenment.

In another, a building that somewhat resembles the US Capitol and a white man in a red jacket, standing next to a statue of Athena, and who may be George Washington suggest – to the very rare, well-informed eye – the prospect of Siam becoming democratic, along with a parallel between America’s first president and Siddharta Guatama.

In another panel, Western doctors and nurses are treating patients in a small park that’s surrounded by fancy European buildings. Again, according to the experts, Mongkut’s intentions in instructing Khrua In Thong to paint such scenes was not just to expose ordinary Thai people to Western culture and technology, but, on a deep, symbolic level, to suggest that traditional Thai beliefs could be integrated into the best of the West, such that Western medical workers were a kind of incarnation of the compassionate Buddha.

There’s also a large painting of Western ships and a whale or shark hunt. This is believed to suggest a parallel between Western exploration and the Buddhist quest for nirvana. It also seems to be a Thai version of the famous 1778 painting, Watson and the Shark, by John Singleton Copley.

And there’s a mural featuring a huge lotus flower emerging from a pond, standing almost like a tree. The origin of this one was probably a false report that an enormous species of lotus had been discovered in Europe. At the same time, the lotus represents Buddha and the entire faith – the idea that we are born in the muck, but have the potential to spiritually flower beautifully.

Most arresting and strange about these murals is the fact that a monk who had never travelled outside of Siam was depicting impressive Western structures, alien technologies, and industrious white people in scenes which bore no obvious relation to centuries of temple murals devoted to scenes from ancient Tipitaka/Pali Canon Buddhist mythology.

Having accomplished my mission, I say goodbye to the monk. The good vibes we had before are all gone. This has all been a dramatic lesson for me, leading to a banal conclusion: Monks are, like priests, as flawed as anyone else.

I was able to spend a lot of time in this extraordinary place, and I got my photos, which led me to study a good bit to get some kind of enlightenment into the very complex iconography of Thai temples.

I wonder what King Mongkut and his favourite temple muralist would think of their young follower in this hidden gem near Bobae Market and the Phadung Krung Kasem canal.

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: