Vietnam: Has America learned nothing from its war of atrocities?

50 years after Saigon fell, the US addiction to war rages on, from Vietnam’s napalm skies to today’s proxy firestorms

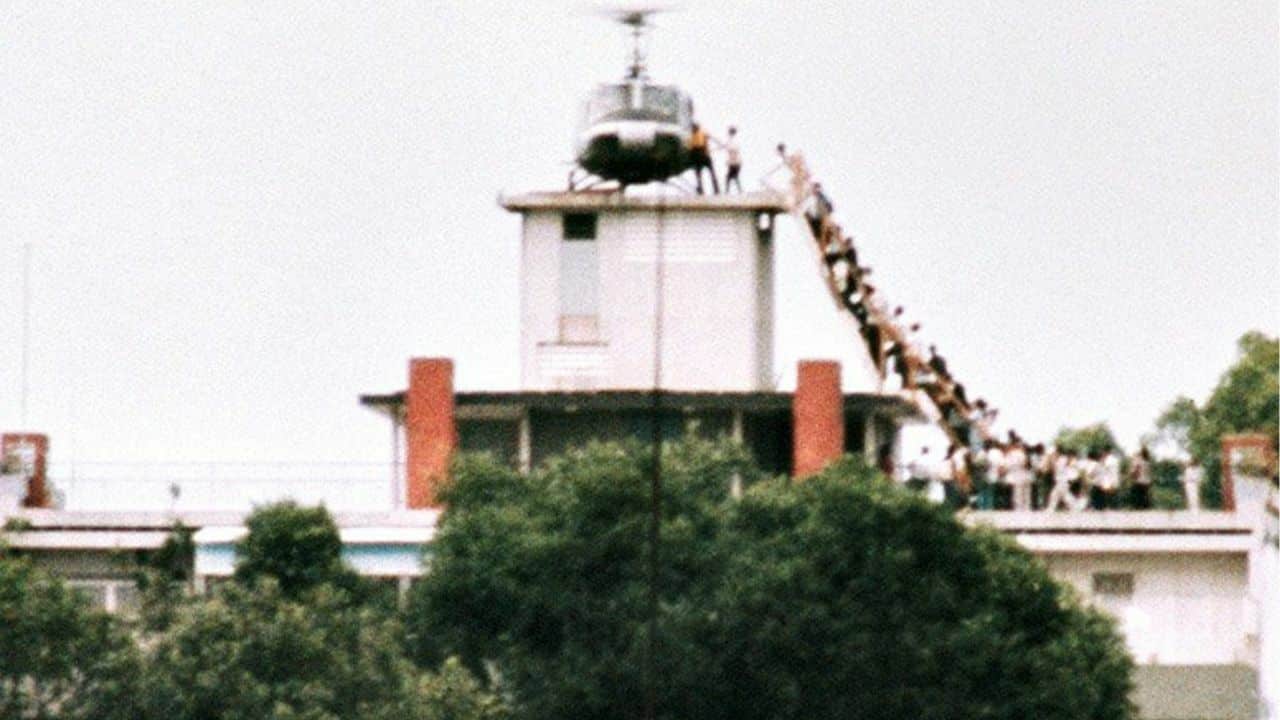

It’s been 50 years since the United States’ chaotic, ignominious final evacuation from Saigon. Images of helicopters atop the US embassy, frantic crowds, and the battered city in April 1975 have become frozen icons of American defeat.

The Vietnam War stands as a testament to the hubris, brutality, and tragic folly of unchecked military intervention, a doctrine the US has seemingly only refined, not abandoned, in the decades since.

The 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War demands not only remembrance but also reckoning. Confronting the enormity of what was done, over three million Vietnamese dead, the toxic legacy of Agent Orange, the deliberate dehumanisation and mass trauma, one must ask: Has America learned anything?

Or have the architects of US foreign policy simply repackaged their errors, now shrouded in the language of “democracy promotion,” “counterterrorism,” and “rules-based order,” unleashing misery anew through proxy wars, covert interference, and steadfast support for atrocities from the Middle East to Eastern Europe?

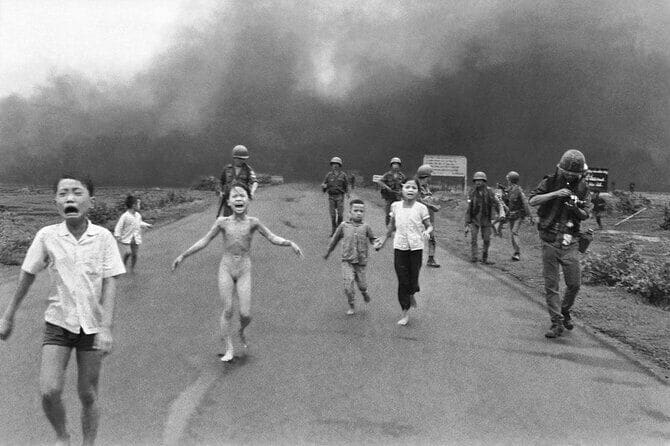

The war in Vietnam was a crucible of horror. Napalm raining down on villages, “search and destroy” operations turning countryside into a graveyard, and the infamous My Lai Massacre, where some 500 unarmed civilians, women, children, and old men, were slaughtered by US soldiers. All were justified by a supposed struggle against Communism, yet all revealed a staggering disregard for Vietnamese life and dignity.

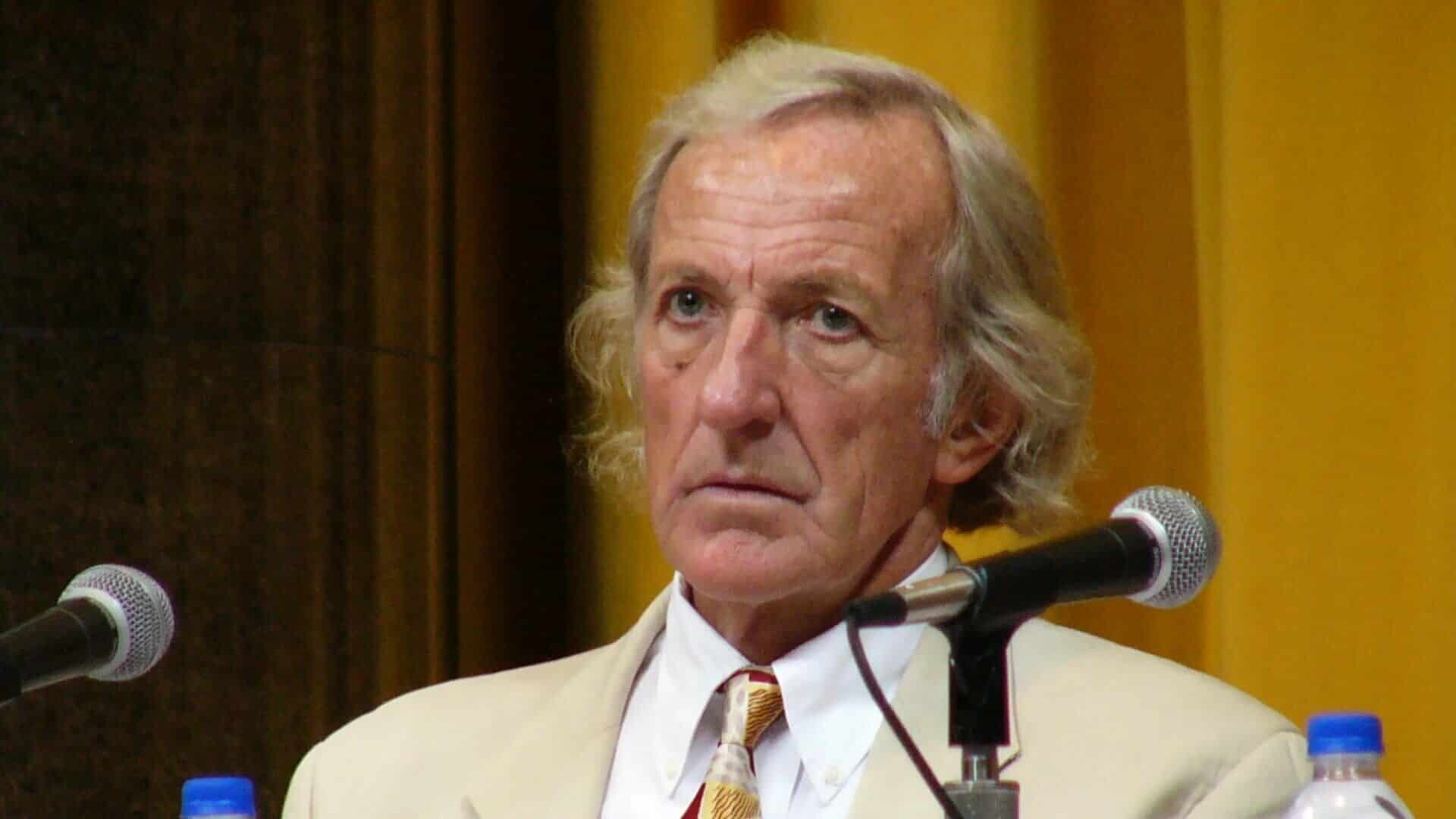

In The War on Vietnam Never Ended, late Australian journalist John Pilger, one of the war’s great chroniclers, highlighted the atrocities

“Vietnam was not a mistake but a crime… hundreds of My Lais happened, in villages with names the world never knew.”

Such crimes were not limited to indiscriminate bullets and bombs. The use of chemical weapons, most infamously Agent Orange, marked a new register of atrocity.

The US sprayed over 19 million gallons of herbicides, poisoning land, water, and generations of Vietnamese. Children born decades later suffer horrific birth defects; cancers and deformities blight the population even now.

The American public, shielded by distance and propaganda, was largely oblivious or indifferent. The war’s carnage was sanitized as “collateral damage,” the Vietnamese dehumanised as “gooks.” The same language and logic are alive today, cloaking new crimes behind digital firewalls and military jargon.

The end of the Vietnam War brought no real soul-searching from American officialdom. Instead, militarism merely changed masks. Whether in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, or Syria, the US repeated many of its Vietnam-era mistakes, escalating violence, undermining international law, and coveting a right to reshape sovereign nations by force or subterfuge.

In an interview with Consortium News, former UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter was blunt in his assessment.

“The United States never came to terms with the reality that its war in Vietnam was immoral. And, as a result, it repeats these crimes, from supporting wars in Iraq and Syria to enabling proxy slaughter in Palestine by Israel today.”

The aftermath of these interventions is visible in shattered societies, endless displacement, and a deepening contempt for Western humanitarian rhetoric.

Whether through drone strikes in Yemen, the CIA’s clandestine ops in Central America in the 1980s, or the US$100-billion flood of weaponry into Ukraine, the playbook remains unnervingly unchanged: demonise the enemy, rally the media, and unleash violence under the banner of moral necessity.

In Vietnam, the war’s legacy is not consigned to museums or academic debate, it is in the breath of the poisoned, and the tears of the bereaved.

Agent Orange’s chemical blight continues to corrupt bodies and ecosystems. The US government, after years of stonewalling, has offered some limited remediation, but no real accountability. For many Americans, the war is a chapter closed, for millions of Vietnamese, it is a wound that will not heal.

As Pilger observed in his 2015 documentary The Coming War on China, “The war on Vietnam never ended, it just evolved.”

“The legacy endured in the suffering of its people, and in the lessons unlearned by those who sent the bombers and chemicals.”

No contemporary conflict echoes Vietnam’s lessons, as ignored as they are, more loudly than the ongoing genocide in Palestine, particularly in Gaza.

Here, American support for Israel’s military campaign, financial, diplomatic, and military, enables devastation on a scale that recalls the most brutal aspects of America’s war in Southeast Asia: the collective punishment, the wanton destruction of civilian infrastructure, the suppression of truth.

In his Project Syndicate column, economist and UN adviser Jeffrey Sachs puts it starkly.

“The US is, by far, Israel’s lifeline in its war on Gaza… This is a test for America’s conscience, and that test is being utterly failed.”

What is repeated is not just violence but also the rhetoric of dehumanisation. As in Vietnam, where the enemy was made faceless and monstrous,

Palestinians today are rendered as animals, threats, collateral, numbers, never victims deserving empathy. Atrocities, strikes on hospitals, schools, refugee camps, are written off as “tragic mistakes,” or “havens hiding terrorists,” just as My Lai once was.

Central to every US-enabled atrocity is the process of dehumanisation.

In Vietnam, Ritter writes, “We began to see not people, but statistics.”

In Gaza, as Sachs and Pilger both note, entire families can be vaporised by a US-supplied bomb, and the news cycle will move on, unless, perhaps, an Israeli or Western hostage is involved.

The Vietnam War’s most horrifying lesson is this: moral barriers can be overcome, and mass murder efficiently sanitised, if only the victims are sufficiently othered. The machinery of US warmongering depends on it.

Aside from the incalculable human cost, decades of US aggression have destabilised entire regions, setting off cycles of sectarian and ethnic conflict, economic devastation, and mass migration.

The US military-industrial complex, invigorated by Vietnam’s “lessons,” now commands an annual budget that surpasses the next nine countries combined. War, once an unspeakable evil, has become normalised, perpetual, profitable.

It is no surprise to Pilger, who mournfully said, “Nothing has changed except the technology of killing and the scale.”

“The mindset remains. Vietnam taught the US military that with enough firepower and a compliant press, they could get away with anything.”

Commemorating the end of the Vietnam War without confronting this unbroken lineage of violence is an act of moral evasion.

The greatest way to honour Vietnam’s dead, as well as America’s own fallen and disillusioned, is to demand that these patterns stop, that the US, at long last, learn that it cannot extinguish fires of its own making with more napalm.

In a Columbia University lecture in 2023, Sachs warned US leaders.

“America’s leaders still believe their nation is exceptional, and mistake that myth for a blank cheque to wage war anywhere. Until this changes, Vietnam’s spectre will haunt the world.”

Fifty years after the last helicopter left Saigon, the lesson is not “never again,” but “how soon again?” After all, the US has an almost yearly trillion-dollar military budget to spend, so why waste it? The root causes of atrocity, arrogance, dehumanisation, impunity, remain entrenched.

If the world is to look back on Vietnam and say something has truly been learned, it will not be through ceremonies or presidential declarations, but through action: opposing new wars, exposing old truths, and humanising those whom power would render invisible.

Only then can the wounds of Vietnam, and of so many others, begin to heal.

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: