Phuket Business: Challenges ahead of ASEAN’s young union

PHUKET: Eliminating tariffs that financially penalize members of ASEAN, is one of the stated long-term goals of the AEC (ASEAN Economic Community).

When economic unions were proposed in the United States and Europe, tariffs became a defining factor that would later determine the outcome of those unions.

Now that ASEAN has decided to form an economic union – the AEC – in order to exert greater regional influence and become more financially prosperous, member states must decide on an effective tariff structure that won’t put any of its 10 member at a disadvantage.

Indeed, this will prove a challenge. The first question is: How will the AEC practically eliminate tariffs and promote equal business opportunities among member nations?

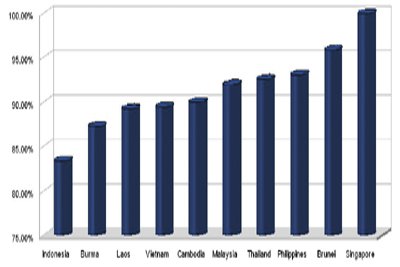

According to the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN (ERIA), a government-funded think tank, the AEC’s goal is to eliminate 95% of tariffs between ASEAN and other countries that it has made Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with.

ASEAN currently holds separate trade agreements with Australia, India, China, South Korea and Japan. These individual agreements between ASEAN and any one non-ASEAN country, are commonly referred to as “ASEAN +1”.

With the AEC’s economic integration deadline of 2015 fast approaching, ASEAN must now decide on how it will approach the daunting task of eliminating tariffs.

A similar case arose when the European Union decided to adopt a single external tariff applied by all of its member-states to imports from non-members.

Internal trade between the EU was aided by removal of barriers to trade, such as tariffs and border controls. The case of the Eurozone was helped further by not having currency differences to deal with.

With ASEAN, according to a recent ERIA policy brief, a “Common Concession” approach is to be applied. This means that: “A country [would] strategically focus its policy discretion [and] allow for sensitive industries on a more limited number of products.

“Assuming 95% tariff elimination is the target, for example, a country can choose up to 5% of (its) products to protect, while opening up the rest [to free trade],” suggest the report’s authors, Yoshifumi Fukunaga and Arata Kuno.

Opening up a product to trade means that no tax, subsidy or tariff will artificially alter the price of production for certain goods.

Such restriction-free trade may lead, some fear, to what is known in financial lingo as “dumping”. According to about.com, dumping is: “An informal name for the practice of selling a product in a foreign country for less than either the price in the domestic country, or the cost of making the product.”

It is illegal in many places to dump products, so that domestic manufacturers are protected from unfair competition.

For example, in Thailand, government subsidies (derived from taxes) help the country to produce rice at a lower price than its actual cost.

However, some experts, such as Jonathan Head, of the BBC’s Southeast Asia Bureau, suggest that subsidies may ultimately wind up hurting the Kingdom in the long run.

He points out that even though Thailand has been the World’s leading rice producer for over two decades, its farmers are as poor and susceptible to weather as they have ever been.

Most economists believe that subsidies are a form of “protectionism” and are inherently bad for trade because they make domestic goods and services artificially competitive against imports. But, Thailand is by no means the only ASEAN country with inward-looking economic policies.

A practical solution, in other words, detailed legislation guaranteeing “open” trade on certain products, will need to be enacted before the union takes effect.

Though few could argue that free trade will hurt ASEAN, perhaps the union should first focus inward, and decide what to do among members before making Free Trade agreements with non-members.

— Chris Hudon

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: