Calvin and Hobbes author comes out of his shell

Millions of fans welcome Watterson’s first major work in nearly 30 years

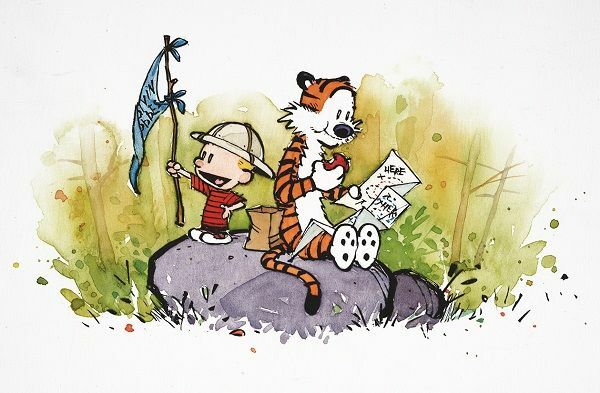

On New Year’s Eve 1995, six-year-old Calvin and his tiger, Hobbes, sledged off together for the last time. It was the final strip in Bill Watterson’s acclaimed comic, Calvin and Hobbes, which appeared in 2,400 newspapers.

The man who had become a cartooning legend all but disappeared, rarely giving interviews. Last week’s announcement of Watterson’s first major work in nearly 30 years – The Mysteries, a fable for grownups – has delighted millions of fans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71979108/CH_reading.0.jpg)

Today’s Guardian asks what prompted Watterson to come out of retirement

Watterson has been described as reclusive, but that might not be the best word. He lives a very normal life, according to those who know him and doesn’t like to be in the spotlight. He’s uncomfortable in the role of a spokesperson for comics and just wants his art to speak for itself.

And many millions of people have been spoken to. Calvin and Hobbes’s books have sold 50 million copies, and the full collection has the unusual honour of having been the heaviest book to reach the New York Times bestseller list (not to mention the most expensive).

Since the strip began in 1985, readers have embraced the adventures of the impulsive Calvin, often lost in a vivid internal world; his thoughtful tiger, Hobbes, who is real to him but stuffed to everyone else; his long-suffering parents; his babysitter and arch-nemesis, Rosalyn; and his bright and diligent fellow first-grader Susie, the target of many a failed snowball throw.

Insightful, wise and appealing

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19964058/ch870324.jpg)

Jenny Robb, head curator of comics at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, said…

“It has everything that can make a comic strip successful. It’s funny, first of all. It’s insightful. It’s wise. It’s visually appealing, particularly in the Sunday strips, which eventually shed the grid layout in favour of panels of various shapes and sizes to suit the story.

“You see him stretching as an artist on the Sundays and they’re just beautiful to look at. So, he brings together all the different aspects of a comic strip, the writing, the characters, the layout, the artwork, and he just has a mastery of all of those.”

Even though we live in a very digital age now, with devices and connectivity that didn’t exist when Calvin and Hobbes were in print, when you read the strips, it’s just a story of a boy and his best friend and the adventures that they went on.

It’s not clouded by pop culture or other references that feel dated. It exists in a place out of time. Kids today who are lucky enough to be given a book or to stumble upon one in the library, love Calvin and Hobbes just as much as when they were first released. The storylines are timeless, and so are the strip’s weightier themes.

Watterson uses Calvin and Hobbes, best friends with opposing personalities:

- to explore the ups and downs of childhood;

- mortality, as when Calvin tries and fails, to nurse an injured raccoon back to health;

- environmental fears (“Sometimes I think the surest sign that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe is that none of it has tried to contact us,” Calvin says);

- horse-race politics, as Calvin reports on his father’s approval rating with polls of “household six-year-olds”;

- consumerism (“Hey Mom, I saw a bunch of products on TV that I didn’t know existed, but I desperately need!”);

- and much more.

Really special, really magical

Robb says…

“I think it demonstrated what was possible with the comics art form, how you can tell stories that appeal to a wide audience with visual variety. These are all things that had been done before. But Calvin and Hobbes brought a lot of unique features together and showed how you could create something really special and really magical.”

As for the next chapter in Watterson’s career, The Mysteries has been described as “a compelling, provocative story that invites readers to examine their place in the universe and their responsibility to others and the planet we all share”, and it “a fable that dares to intimate the big questions about our place in the universe.”

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: