Master of Fine Arts in motion: Thailand’s oldest art school reinvents the future

An interview with five artists explaining how heritage, philosophy, and experimentation are reshaping Thai art today

The Thaiger key takeaways

- Poh-Chang Academy of Arts, Thailand’s oldest art school, has launched its first-ever Master of Fine Arts programme.

- Five pioneering students are blending centuries-old traditions with modern concepts, from repoussé metalwork to experimental jewellery.

- The programme signals a shift in Thai art education, redefining the line between craftsman and artist while pushing boundaries of expression.

If Thailand has a Louvre, it’s not in a gilded palace or a tourist-saturated temple. It’s on a campus where the air smells faintly of turpentine, where students still carry sketchbooks, and where the word ‘craftsman’ (Chang) has been passed down for generations like a family heirloom.

That place is Poh-Chang Academy of Arts. Founded in 1913, it holds the distinction of being Thailand’s oldest art school. For more than a century, it has trained painters, sculptors, carvers, and craftspeople in traditional Thai arts.

And now, for the first time in its history, Poh-Chang is offering a Master of Fine Arts programme. A leap into the 21st century that signals not just a new degree, but a new vision for what Thai art can be.

Think of it as a high-stakes experiment: what happens when centuries of tradition meet a generation of artists who don’t just want to make beautiful things, but want to ask dangerous questions like, What is art? or Does my audience even matter?

To find out, we spoke with five of the programme’s first students. Their stories reveal both the weight of tradition and the restless ambition to break free from it.

Artists of the Master of Fine Arts programme

| Artist (Click to jump) | Summary |

|---|---|

| Punpaphob Wanaprasertsak | A weekend commuter who blends Thai and Western imagery into abstract forms, focused on ideas over rules. |

| Jirakron “Yo” Pitakpongsa | An artist who revives repoussé metalwork with Buddhist and Taoist philosophy, urging effort over prayer. |

| Pipatphong “Palm” Ratpakdee | A woodcarver balancing tradition with modern thought, aiming to make the past speak to today. |

| Kritsanaphorn “Nut” Meehongthong | A jewellery designer breaking free of wearables, exploring art as joy and meaning beyond decoration. |

| Jib Blouin | With her embroidery and painting background, she is now exploring the shift from craft to art through concept-driven work. |

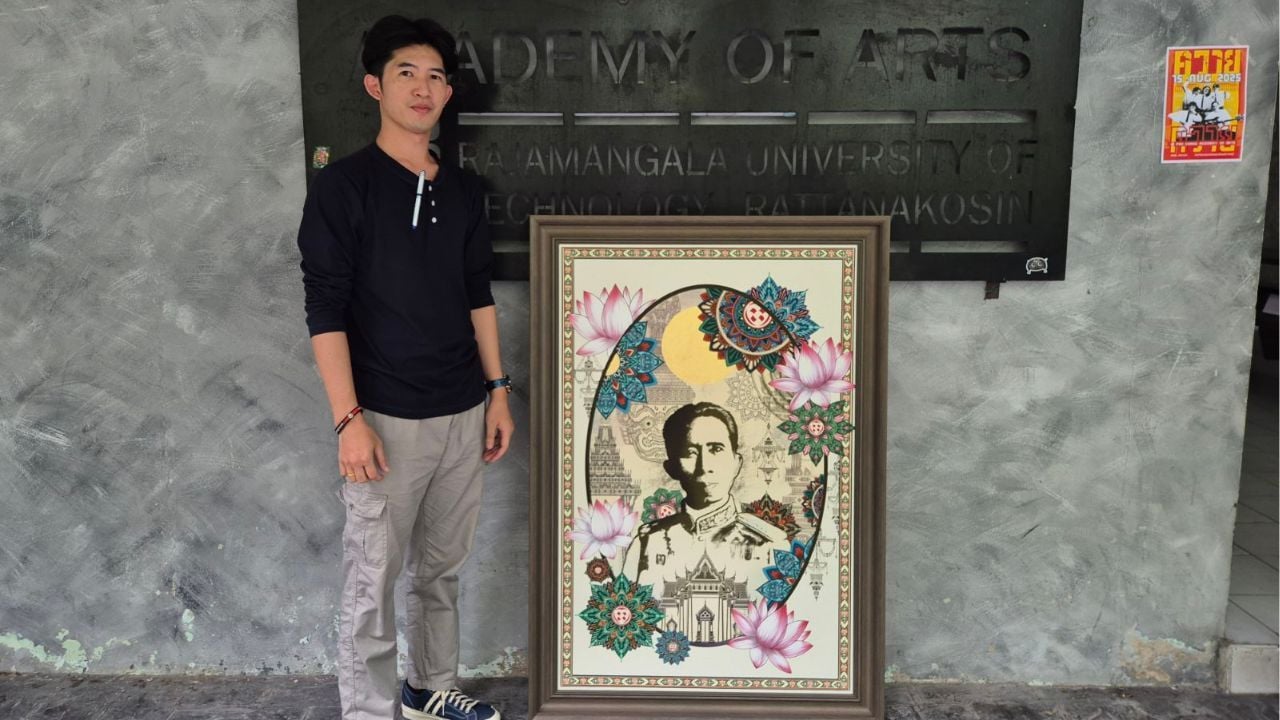

Punpaphob Wanaprasertsak: The Weekend Warrior

If art is a passion, Punpaphob has turned it into frequent flyer miles. He works full-time in the south of Thailand during the week, then flies all the way to Bangkok every weekend for Master of Fine Arts classes. By Monday morning, he’s back at his day job.

Interviewer: So, what is the art style you are creating while studying in the programme?

Punpaphob: “It’s a mixture of Thai and foreign images, but the mixture that I want to create is an abstract piece. Normally, my art focuses on creating quote marks. You know what I mean, right? I want to take that further, to improve it and develop it uniquely. There are so many rules in traditional Thai art. The colours, the patterns, even the shape of the marks themselves,

“I respect those rules, but I also want to expand them and create something more personal, something that carries my own sense of uniqueness. For example, the piece I showed you is a mix of the traditional quote mark style combined with the face of Professor Kuroda Furoshi. That’s how I want to express my work, not just as traditional Thai art, but as a blend of Thai and Western styles.”

Interviewer: So, how does this programme in particular help you be able to express yourself that way?

Punpaphob: “For me, the most important part isn’t just developing technical skills necessarily. Here I can focus on the process of thinking. That process gives me the freedom to create my work openly, guided by a concept rather than restricted by rules.”

A Poh-Chang alumnus, Punpaphob, says he came back to “break his own wall.” His work blends Thai and foreign imagery into abstract compositions that respect the rules of traditional Thai art but deliberately bend them. For him, the MFA is less about honing skill and more about sharpening thought.

And when asked if he worries whether audiences will accept his experiments? He shrugs it off: “It’s not my job to care if they like it or not.” True artist energy.

Jirakron “Yo” Pitakpongsa: The Metal Mystic

Yo works in repoussé, an ancient metalworking technique passed down across Asia from India to Burma to Laos. Each different culture adds its own flavour to the technique. Once reserved for royal crowns and jewellery, he’s now reshaping it into contemporary pieces with modern meaning.

Interviewer: I hear you are learning something unique from this new programme.

Jirakron: “Yes, in this school, I’ve been learning an ancient metalworking tradition that most people don’t even know exists. My goal is to bring more awareness to this art form. I’m not sure what it’s called in English, but it involves working with a metal plate pressed against a softer material. In Thai we call it “Khit Ngan Loi” (ขิตงานลอย) (repoussé in english)

“I shape it from the back, curving and pushing until the design slowly takes form. Then, when I lift it up, the front reveals the face of the piece. In Thailand, only a small group of people still practice or even care about this method. That’s why my goal is to share it more widely to help people recognise and appreciate this type of work. Here, everyone knows about mural painting and sculpture, but very few know about this art.”

Interviewer: You seem to have a philosophy behind your work. What is it and what does it mean?

Jirakron: “My philosophy is shaped by both Taoism and Buddhism, specifically Theravāda and Mahāyāna. But my work isn’t about showing monks or Buddhas as figures of authority, leaders, or divine givers of blessings. What I want people to understand is that everyone has to try for themselves. It’s not just about asking for blessings or praying for good fortune,

“That’s why I don’t want my art to simply depict an Indian god, or a Buddha surrounded by people begging for favours. Instead, I want my audience to come away with the idea that they, too, must put in the effort. That hard work is part of the path. My art should remind people that change and growth don’t come just from wishing, but from what we do ourselves.”

His goal is simple: revive an old technique, but let it speak to today. Instead of repeating decorative patterns, he injects Buddhist and Taoist philosophy. Yo doesn’t want audiences to bow to his work like it’s a statue of Ganesh; he wants them to walk away, realising that success isn’t prayed for, it’s earned.

For him, the Master of Fine Arts programme provides the only platform in Thailand where traditional methods are taught alongside contemporary thinking. It’s not just metalwork, it’s metalwork as a moral compass.

Pipatphong “Palm” Ratpakdee: Balancing Act

If Yo is about transformation, Palm is about balance. A full-time wood carver and restorer of Thai treasures (yes, the kind that end up in royal collections), he has one foot firmly in tradition. But at Poh-Chang, the Master of Fine Arts classes are forcing him to plant the other in contemporary theory.

Interviewer: So, you study wood carving. How does this programme teach you differently from others?

Pipatphong: “This programme really helps me develop my work. Art has many aspects, and through this programme, I’ve learned how to adjust both the way I think and the way I work across different directions. Every piece starts with many lines and many thoughts, and this training has given me tools to explore that process more deeply,

“What I’ve gained the most here is a way of thinking, learning to design and plan before I begin creating. The school teaches traditional methods, but at the same time, they allow us to approach them in a more contemporary way. That balance between tradition and innovation is what I value most.”

Interviewer: We live in contemporary times, and many students, including yourself, are learning traditional conservative art forms. Do you think you have a challenge ahead?

Pipatphong: “I make art that carries meaning, and for me, that’s always a challenge. Everyone today is searching for something new, but I believe we also need to look back at the old. We have to return to the past. Study it, question it, and figure out how to make the new generation understand it. That’s the challenge I face,

“In the art world, people often tell me it’s all about moving forward, always chasing the new. But in my small circle, conservative restoration art. We work in the opposite direction. We go back in time, trying to uncover and understand how things were once made. We study the process, the methods, and then we find ways to teach others. For me, that act of going back to move forward is the real challenge.”

Thai woodcarving, he explains, is defined by the idea of making “hard things look soft.” Palm takes that concept and asks: how can something ancient survive in a modern world obsessed with novelty?

His mission is to create a bridge, art that retains the discipline of tradition while speaking in a language contemporary audiences can understand. “Everyone is looking forward,” he says, “but we also have to look back.”

Also: Why trucks and buses in Thailand are moving works of art

Kritsanaphorn “Nut” Meehongthong: Escaping the Jewellery Box

Nut comes from jewellery design, but she isn’t content making necklaces and rings. For her, the Master of Fine Arts programme is a chance to step out of the “safe zone” of design and use her training as a launch pad for art that expresses something deeper.

Interviewer: What are you trying to accomplish in this new programme?

Kritsanaohorn: “I want to move beyond the safe zone of jewellery design. Rings, earrings, necklaces. Those have already been done countless times. I don’t want my work to be limited to just another jewellery piece. Instead, I want to explore new ideas and concepts, to take what I’ve learned from my background in both jewellery and CAD design and push it further. My goal is to create art differently, not just wearable objects, but pieces that open up new possibilities and perspectives.”

Her vision is still forming. She admits she hasn’t found her philosophy yet, but she’s certain about two things: she wants her work to bring joy, and she wants it to carry meaning beyond decoration. In other words, not just shiny objects, but ideas made wearable.

It’s art as escape, art as experiment. And for Nut, that’s worth the risk.

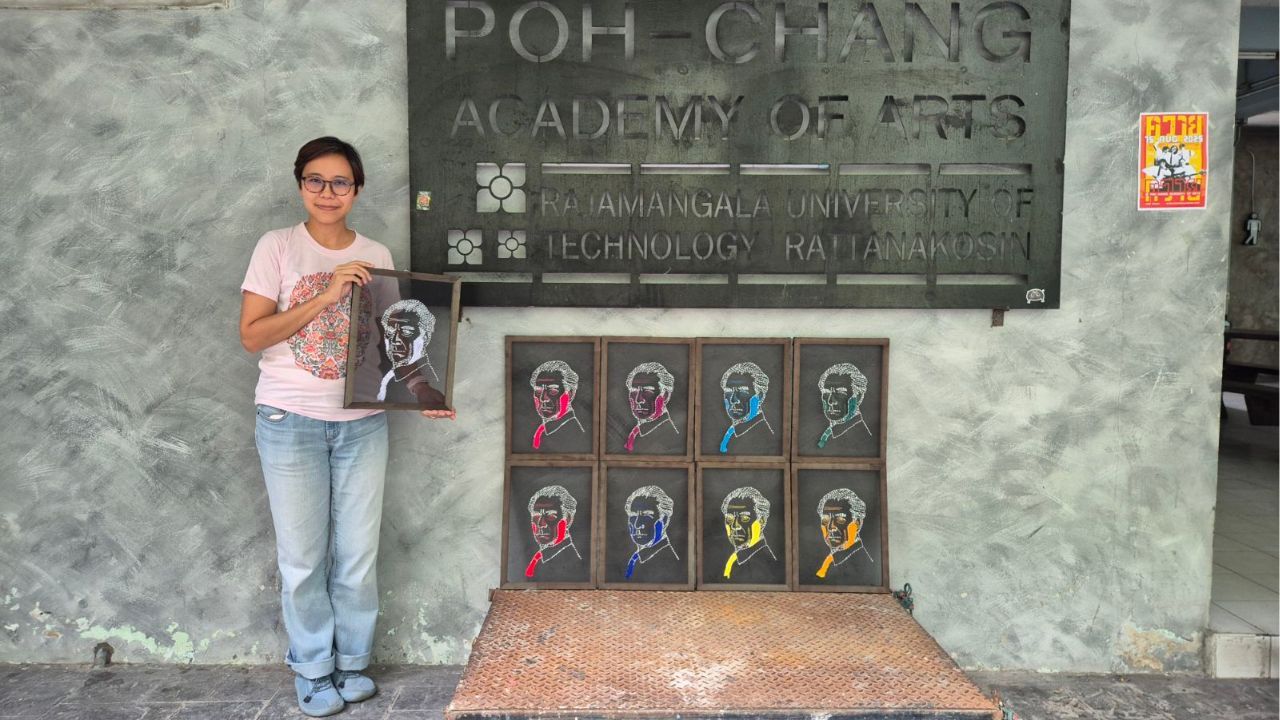

Jib Blouin: From Craftsman to Artist?

Finally, there’s Jib, who may be the purest embodiment of what this Master of Fine Arts programme is trying to do. She trained in traditional Thai embroidery and painting, where graduates are taught to call themselves not artists, but “craftsmen.”

Interviewer: Why did you choose this programme? What does it offer you?

Jib: “I’ve always asked myself, ‘What is art?’ And how can I truly become an artist? I graduated from the Royal Academy of Art, where I studied traditional Thai styles. But there, we never called ourselves artists. We were taught to think of ourselves as craftsmen. Skilled, yes, but not artists,

“That left me questioning: what’s the difference? I know I have the skill to paint a mural, I can do it well, but does that make me an artist? I’m not sure yet, and that’s something I want to understand. It’s one of the main reasons I came into this programme. I want to explore that line between craft and art. Because in my work, I create both. I carry many skill sets, but I’m still searching for what it means to call myself an artist.”

Interviewer: How do you think this programme can help you with this conundrum?

Jib: “Well, now, every piece of my work begins with a concept. Something I’ve developed through classes and guidance from my professors here. Creating a hope that when people see my work, they can immediately understand what I’m trying to express, without needing to read a description. Ideally, the piece should speak for itself. That’s my goal I’ve created: for the audience to feel the meaning just by standing in front of it,

“Coming from a background of traditional craft, I used to think art had to be something beautiful. Something you look at and immediately call “art.” But since joining this programme, my perspective has changed. I’ve learned that anything can be art, depending on the idea and the process behind it. That realisation opened a completely new world for me, and it’s exciting to see how quickly the art scene in Bangkok, and even across Thailand, is growing in that direction.”

“What is art?” It’s a question she carried for years, and the MFA is her attempt at an answer. At Poh-Chang, she’s discovering that art isn’t just a skill, it’s a concept. She no longer wants to create something just because it’s beautiful. She wants her work to speak without a caption, to carry meaning.

With Jib, you can see the shift: the craftsman searching for a new identity in a country where the line between art and craft is being redrawn.

The Future of Thai Art

Together, these five voices paint a picture of Thailand’s artistic crossroads in not just education, but its art scene as a whole. Tradition is not being abandoned, it’s being reimagined. Metal, wood, jewellery, mural, and embroidery: all are being tested against modern questions of philosophy, audience, and meaning.

Poh-Chang Academy of Arts may be over a century old, but with its new Master of Fine Arts programme, it’s asking very contemporary questions. The answers will come from artists like Punpaphob, Yo, Palm, Nut, and Jib. Artists who are willing to fly every weekend, bend old rules, escape safe zones, and even question whether they can even call themselves artists at all.

And maybe that’s the point. The future of Thai art isn’t about being certain. It’s about asking the questions loud enough that the answers echo back.

Also: Museums and art spaces in Chiang Mai

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: