Trying to find a pulse in Thailand’s economic health

Thailand’s economy is south-east Asia’s wounded soldier as the newly elected Thai government tries to boost confidence and stimulate the economy after five years of military rule. Certainly the past 12 months have been the most challenging.

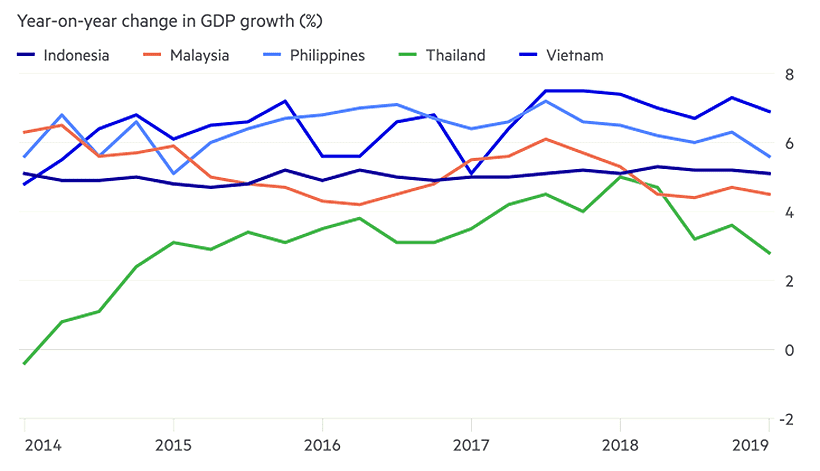

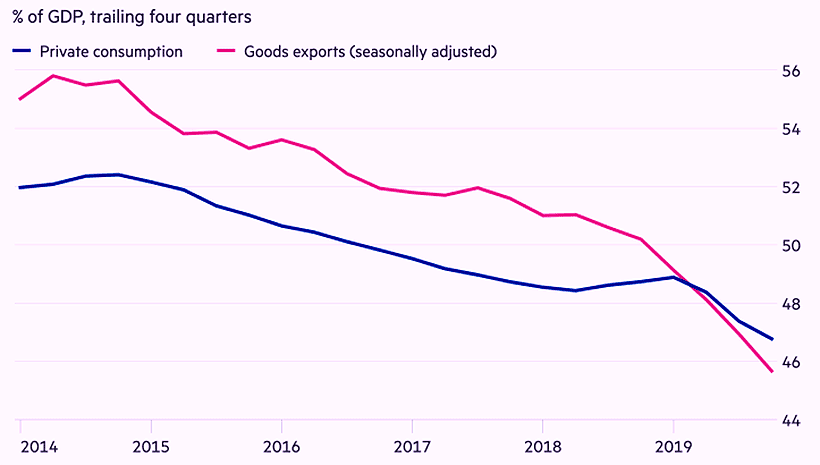

GDP growth hit a four-year low of 2.8% for Q1 2019 and exports remain weak.

Despite having unlimited power for half a decade, PM Prayut and the NCPO have done little to improve Thailand’s economic situation or the plight of the average Thai.

Going after the previous premier and the elected Pheu Thai government as soon as they came to power over a rice pledging scheme (subsidies for rice farmers), the NCPO have used the same blunt tool of agricultural subsidies to keep the northern and north-east farmers ‘happy’. After all, that was Prayut’s big promise after seizing power in 2014, “bringing happiness back to the people”.

Big infrastructure promises and spending have made good headlines but are yet to show any economic gain for most Thai people. It hasn’t really made Thai people ‘happy’ yet.

Of the ASEAN 5 economies (Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines and Thailand), the Land of Smiles has performed the worst over the fast five years averaging 3.6% growth against the average of the other four nations of 5-6.2% GDP growth.

For 2019, Thailand’s National Economic and Social Development Council, responsible for calculating the official GDP figures, has set growth at 3.3-3.8%, down from 4% estimated at the start of the year. If the tourist tap stops gushing and slows to a trickle and the export figures keep trending down, the estimates may have to be revised down further again.

SOURCE: Global Economic Data, Indicators, Charts & Forecasts

Following the election and the (soon) completed formation of the new government it would appear that political stability abounds for Thailand but the fragile 19-party coalition is not predicted to last long. It’s also considered unlikely the new PM, who is the old PM from the five years of military rule, will be a fan of lengthy discussions, public consultation and parliamentary debate. Some of the smaller parties, who threw their weight behind the pro-junta coalition initially, are now getting flakey and looking to cross the floor and take their place in the back-benches of the opposition side of the new parliament.

Public debt has also steadily risen under military rule, climbing to 34% of GDP last year from 30% when they came to power. But international credit rating agencies are not ringing alarm bells just yet and Thailand’s public debt levels remain lower than Vietnam, Malaysia or Indonesia.

Thailand’s two largest infrastructure projects will surely continue to manifest, though the next phases of the contract will now be subject to debate in the new parliament. These include the 225 billion baht high-speed rail link between Suvarnabhumi, Don Mueang and U-Tapao international airports, and the China-backed high-speed line between Bangkok and the Thai-Laos border with a proposed budget of 300 billion baht.

And the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), the expansion of industry for the areas from Bangkok’s east to Rayong, will remain a showcase for economic growth for the new government.

Thailand will now have to choose whether it’s sufficient to keep surfing along as the wounded soldier of south-east Asian economies or whether it can muscle its way back to a position of regional economic prominence.

SOURCE: National Economic and Social Development Council

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: