Clawing back the tiger population

(10 minute read)

The plight of the Indochinese Tiger is a particular passion for The Thaiger. As a leading sponsor of SaveWildTigers.org we applaud all the work being done in Thailand and around South East Asia in support of the survival of the species.

By Piyaporn Wongruang

Ahead of the Global Tiger Day on Sunday, July 29, lead tiger researchers and advocates come together to address critical threats against tigers as much as means to help conserve them.

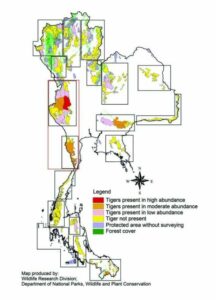

Despite receiving good news that at least 10 to 15 tigers have been found roaming in the Thap Lan and Pang Sida national parks, lead tiger researcher Somphot Duangchantrasiri is concerned that in these same areas, poaching as well as illegal logging of Rosewood is rampant.

While Somphot and his colleagues have been working to study and conserve the species, the number of foreign loggers has grown from tens to hundreds, posing a direct threat to the animals. The complex – a part of the Dong Phaya Yen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, the country’s second natural World Heritage Site on the East – is acknowledged as the second-last hope to provide a safe home for the tiger, after the success at the country’s first natural World Heritage Site of Thungyai-Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuaries on the West. There, the tiger population has been closely monitored and protected by Somphot’s prime wildlife research station, Khao Nang Ram.

Tiger numbers have declined by around 97% over the past hundred years. At the beginning of the 20th century there were an estimated 100,000 tigers. Now, fewer than 3,200 remain in just 7% of their original habitat. There are now more tigers in captivity than in the wild.

Realising the emerging threat, Somphot does not hesitate to rush his team’s efforts to study the tiger population in detail, patrolling hundreds of kilometres of the complex, and using camera traps to capture and locate the tigers to identify and record their movements. He hopes that the new body of information they collect about the tigers in the area will help lead to proper management and protection measures, such as those introduced at Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai that have resulted in the tiger population now growing to about 60. An even better result would be if the tigers could roam out of the forests, cross the main Highway 304 into Khao-Yai National Park, and replenish the population there, which has been absent for years.

“What we are seeing from our decade-long study of tigers is that they are moving in areas other than just the Western Forest Complex. This tells us how critical it is for the forests to be restored or protected for us to reintroduce the tiger population,” said Somphot, now chief of Khao Nang Ram.

The fate of tigers – the top species on the forest food chain and thus a prime indicator of the health of the forest ecosystem – would not have received public attention if it had not been highlighted at the St Petersburg Tiger Summit in 2010, where Thailand was recognised as one of 13 tiger range countries that were requested to work on the plight of tigers and help improve the global population that has plunged from around 100,000 to below 3,500.

The summit saw a new commitment among the tiger range countries to double tiger population by 2022 under the Global Tiger Recovery Programme. Under the programme, Thailand has come up with the Tiger Action Plan 2010-22 to meet the goal.

In 2016, the plan was adapted into the new 20-year strategic plan for tiger population recovery, which has set key prime strategies to reintroduce the tiger population in Thailand, including in-depth research and studies to help guide management and protection.

On the ground, a small group of researchers from the Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation (DNP), as well as others from organisations such as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), had been studying tigers for some time before that. In the mid-1990s, the DNP’s tiger researchers, Dr Saksit and Achara Simcharoen, started studying leopards in Huai Kha Khaeng before expanding their research into tigers when Saksit became a chief of Khao Nang Ram. In the mid-2000s, tigers were used as one of four flagship species to help guide conservation intervention measures for better protection and management of the forest ecosystem as suggested by Dr Anak Pattanavibool, who was a director of the WCS Thailand program at that time.

By using tigers as a prime ecological indicator, recognised as a living landscape species, the study could not only point to their survival but also help assess the health of the ecosystem and guide other conservation work to correspond to the needs of the survival of the species. Somphot, who succeeded Saksit at Khao Nang Ram and has continued the study there, said the occupancy research is conducted as an umbrella study to scan areas where traces of tigers may be found and help locate their presence and distribution.

Of about 18,000 square kilometres of the whole of the Western Forest Complex (Wefcom) – where about 4,000sqkm of Huai Kha Khaeng and Thung Yai Naresuan acts as its heart – wildlife rangers were sent out to patrol the area to collect any traces of tigers, their food sources, as well as any threats.

Forests, the experts said, should be managed in clusters so that management is collective and progresses in the same way. Besides area management, a fresh idea of releasing captive tigers into the wild has also been suggested. Long-term tiger researchers disagree with this, however, fearing that their behaviour could become harmful after their releases. Experts believe that once they are returned, they could harm people, rather than running deep into the forest to breed, and the years-long efforts in tiger conservation would collapse following the loss of credibility of tiger conservation.

Anak of the WCS Thailand program, and a member of the sub-panel under the natural resources and environment reform committee, said that releasing tigers into the wild is hardly a success story in the world and hardly anyone does it. He said Russia has managed to release two tiger cubs into the wild, but they were actually born in the wild but left by their dead mother. The cubs, he added, were well taken care of without human contact and did not lose their instincts.

Anak cited the importance of the disconnected and degraded forests that could be restored to serve tigers again, but critically the strengthened efforts on protection have proved to be successful in bringing tigers back and boosting their numbers. It is not only about returning the tigers, he said, but once the areas are safe enough, their prey will also return and other suitable ecosystems necessary for their survival.

The success story recently occurred in Thung Yai Naresuan East, where communities inside the forest were relocated, and wildlife, including tigers, have returned and reproduced there. “Only one bite will wipe out years of conservation efforts and we need to carefully think about it when, positively, we have seen their numbers are growing here. The challenge is how we can bring back their prey, their ecosystems and such. That is what needs to be done here,” said Anak.

Read the rest of the story at The Nation HERE.

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: