‘Leaving Thailand’ – From Phuket with love and heartaches

“In his new memoir “Leaving Thailand,” a former journalist, film tech and Phuket resident looks back on his life and loves in the kingdom that continue to haunt and inspire him.”

By Jim Algie

I’m wary of memoirs set in Thailand in which a sex-starved Western man descends on the country to get caught up in the carnal circus of bars, bargirls, sex tourists, wastrels, pleasure-seekers and those eccentric expats I call “Bangkooks”.

But Steve Rosse quickly differentiates himself from the herd in the first story, “A Woman of Bangkok,” by noting how he stumbled upon the famous novel “about a young Englishman who falls in love with a Thai ‘dancing girl’ in Bangkok circa 1950. She takes all his money, breaks his heart, costs him his job, and finally leaves him to a future of failure and bitterness. But despite its turgid plot, the book is brilliantly written. It is a story full of wit, pathos and plain old human drama, and it’s one of my favorite books in the world.”

I quote this passage at length not only because it sums up the story arc of so many Thailand books, but also because Rosse brings many of the same qualities, like “wit, pathos and plain old human drama,” which are the lynchpins of Jack Reynolds’ book, to these stories. The effect is a fresh take on a hoary genre that quickly morphs into something much more substantial and distinctive.

In the early parts, however, the blow-by-blow descriptions of the harlots-for-hire scene on Phuket around 1990 are tastefully done and largely sympathetic to the women. As a student of both Thai language and culture, Rosse casts himself as both participant and observer. By straddling that divide, he brings plenty of universal observations about life and hedonism to this specific milieu: “Everybody bears some burden of self-loathing, and for some that burden is so heavy they will only allow themselves joy if it’s connected to an act of penance.”

From the nether regions of Phuket the memoir scales the heights of high-society after the narrator, despondent about breaking up with a bargirl, marries a respectable Thai lady he doesn’t love and starts a family.

Now working in a five-star hotel, Rosse’s depiction of his life as a PR shill is both candid and comedic: “Normally I would greet a VIP in the lobby and walk him to the dining room, doing the warm up jokes on the way. Find out if the VIP has enough English for the intellectual jokes or if I would need to stick to jokes about farts. Settle in over appetizers and aperitifs, laud the hotel, hand out business cards, and then when the food hit the table ask for my photo opportunity.”

In one of the most memorable tales in “Leaving Thailand” (available from Amazon as an ebook or paperback), the author develops an unlikely friendship with their young nanny from Myanmar, both of whom have been tyrannized by Steve’s wife. (“A 38 year old man and a 13 year old girl. We were Vladimir and Estragon waiting for Godot in an empty, sterile, existentialist landscape.”)

But the story’s strong suit is that it plays out against a far bigger backdrop than the Phuket setting across a much wider swathe of personal history. In 2003, now in Iowa with his wife and children, the author took out a classified ad in The Phuket Gazette to try and track Pui down. The search results were zero.

Along the lines of JD Salinger’s classic short story, from which the title “For Pui with Love and Squalor” is taken, the friendship between Steve and Pui breaks free from the constraints of time and geography to float in a timeless realm. Sure, the particulars may have changed a little, but since maids and nannies from Myanmar remain fixtures throughout Southeast Asia, the story’s huge heart still pulsates with vitality.

In both Thailand and the US, the author covers plenty of ground. He takes a long trip up north to go trekking and smoke opium with a hill-tribe, which used to be a rite of passage for many backpackers. Once again, the story is not without its blackly comic interludes. When the author arrives back at JFK in New York an opium pipe he’d bought as a souvenir and forgotten about falls out on the table when the Customs agent searches his bags. After whisking him off to the back room for a personal search, he writes, “I told God, ‘Dear God, if you keep this cop’s finger out of my ass, I promise I’ll go back to Thailand and study Buddhism.”

There’s also a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the Oliver Stone movie, “Heaven and Earth.” Steve was the Head Set Dresser, and the only foreigner working on a team of nine Thai men. It’s another autobiographical piece in the collection with much grander ambitions than mere diarizing. In one passage he skewers the foreign stereotype of lazy and unreliable Thai male workers; these guys are both diligent and resourceful. In another, he conveys the main drawback of being an expat stranger living in very strange lands.

“And after two years of being the farang in Thailand, always being just outside the conversation, always trying to learn the rules and not accidentally insult anybody, always paying more for everything, it felt good to finally be on the team.”

For me, the most captivating story is “Cellies.” It starts in Iowa at a high-school graduation party in a bean field, illuminated by the lights of pickup trucks and energized by kegs of beer. Coming home from such a party, similar to one that Rosse attended, a blonde cheerleader is paralyzed for life when her boyfriend rolled his pickup on the way home.

Dorothy ends up in a nursing home across the street from the house where Steve grew up. After returning from Thailand in 1997 with his wife and two kids he winds up living in the family home again.

The contrast between all the developments in his own life, going to university then working in the film biz in New York, travelling all over Thailand before his bittersweet homecoming, and the details of Dorothy imprisoned in that nursing room, unable to move but still possessing the gifts of speech, sight and hearing, is both a devastating juxtaposition of parallel lives and a considerable feat of empathy for this hapless woman.

Hemingway famously said that the best stories are like icebergs; the biggest parts of them float beneath their surfaces: “The Old Man and the Sea” isn’t just about a fishing trip, right?

“Cellies” put me in mind of that quote, but also my hometown in Canada and all the old friends who never left. Maybe they were paralyzed by a lack of curiosity about the bigger world or all tied up in the straightjacket of a 30-year mortgage. I don’t know. It’s an open-ended kind of story. Do your own reading and choose your own interpretation.

For the most part, the stories unfold in chronological order. Towards the end, however, the author’s reflections span the vast gulf of nowadays and yesteryears after a return trip he made to Thailand in 2019.

Full of articulate and realistic stories written with candour and humour, the collection is a worthy non-fiction successor to “A Woman of Bangkok” told by “A Guy on Phuket,” who, despite the book’s title, never really left the kingdom.

Jim Algie is the author of the nonfiction collection “Bizarre Thailand” and the more recent book of music journalism and literature, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of Rock and Punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway.” Both are available from Amazon.

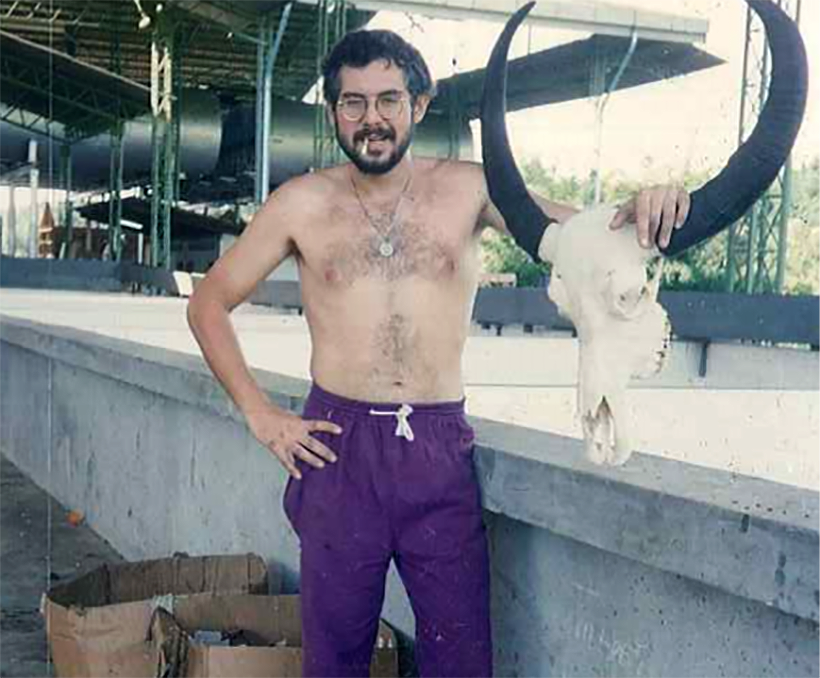

The author, Steve Rosse

Latest Thailand News

Follow The Thaiger on Google News: